Clara Anna Hatton (1901-91)

Clara Hatton, 1934

Clara Hatton’s story begins and ends in Kansas. The oldest of six children, Hatton was born in a modest wood-frame house and raised on a farmstead in Russell County, Kansas, near Bunker Hill. She died in Salina, Kansas, where she spent the last two decades of her life after retiring from Colorado State University in Fort Collins.

Hatton’s parents, Apollonia (née Klein, 1882‒1980) and Lemeon “Lem” Hatton (1873‒1938), were first-generation Kansans. Their parents were part of the western migration of white easterners and European immigrants that came to Kansas in the wake of the Homestead Act of 1862, hoping to claim a quarter section (160 acres) of land. According to Hatton family lore, Apollonia’s family came to America from Austria seeking work in the coal mines of Kentucky before going west to Kansas. Census records indicate that Johan Klein (1837‒1924), Apollonia’s father, was born in Hungary and immigrated to Ohio before moving to Kentucky and then to Kansas, where he built a homestead on a claim in Russell County. Born in Kentucky, Lem’s father, Wesley Graham Montgomery Hatton (1840‒1923), first came to Kansas with his parents in 1859, when they moved to Jefferson County, in the northeast corner of the Kansas Territory. By 1874 he was living on a claim in Russell County, where he would build the homestead on which Lem was raised.

Around 1900, the year Apollonia and Lem were married, Lem purchased a 160-acre piece of land adjacent to the east side of Wesley’s quarter section. This is where Clara Hatton was born and raised. Eventually, Apollonia and Lem’s burgeoning family became more than their small wood house could contain. In its place, Lem built a massive, two-and-a-half-story house and a large barn, both of which were constructed of locally quarried limestone. Today, the land on which the Hatton farmstead stood is submerged under Lake Wilson, a reservoir constructed in the early 1960s. As an artist, Hatton often turned to her native Russell County for subjects for her prints. For example, Hatton’s etching Yucca and her woodcut Warner’s House (Early Settler’s Home) depict views near the Hatton farmstead.

Hatton family farmstead, Russell County, Kansas, 1950s

Clara Hatton, Yucca, 1937, etching on paper

Clara Hatton, Warner’s House (Early Settler’s Home), ca. 1937, woodcut on mulberry paper

Culture and education were high priorities in the Hatton household. Apollonia saw to that, paying for the childrens’ tickets to the Lyceum, music lessons, and art supplies with money she earned by doing laundry for Bunker Hill residents. All of the Hatton children graduated from high school. Clara excelled at her studies, graduating valedictorian of the Bunker Hill High School Class of 1919. Following graduation, she attended a teacher certification program at Fort Hays Kansas State Normal School (now Fort Hays State University) during the summers of 1920 and 1921, teaching at the one-room country school in Success, Kansas, and at the elementary school in Bunker Hill.

Clara Hatton with students, one-room schoolhouse, Success, Kansas, ca. 1920

An artistic polymath, Hatton had an impressive command of a wide variety of media, including: bookbinding, calligraphy and lettering, ceramics, metalwork, oil painting, printmaking, watercolor, and weaving. In 1922 she began her studies at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, enrolling in the Art Department of the university’s School of Fine Arts, where she earned a BA in design (1926), a BFA in painting (1933), and was an instructor in the art department (1925-1936). The department’s faculty recognized Hatton’s potential as a collegiate teacher her junior year, when they hired her as an instructor in design, a position she held for the remainder of her time at KU. The school’s primary objective was to train professional musicians and visual artists who could teach and practice their art in communities across the state. The Art Department boasted a faculty of five professors, capacious facilities, and ample equipment, including: seven large studios with skylights; 100 plaster casts for drawing classes; professional models for life drawing; a clay modeling room; facilities and equipment for grinding and mixing clay and porcelain; bookbinding equipment; tools for metalwork and jewelry in silver and copper; examples of original Coptic fragments for the study of design; a slide library for teaching art history; and an art library containing over 2,000 volumes.

Hatton’s mentor at KU was Rosemary Ketcham (1882‒1940), an Ohio-born artist hired in 1920 to teach design at KU. Before coming to Kansas, Ketcham taught at Syracuse University in New York, where she was one of the founding faculty members of the school’s design department. Ketcham was an early adherent of Arthur Wesley Dow (1857‒1922), the American painter, printmaker, and art educator. Dow’s ideas about art gained widespread currency among American art educators with the appearance of his influential book Composition: A Series of Exercises in Art Structure for the Use of Students and Teachers, first published in 1899. At the core of Dow’s teaching was his belief that composition, the process of harmoniously arranging formal elements (line, mass, color), and not drawing, was the “fundamental process in all the fine arts.” Dow’s thinking challenged the traditional academic emphasis on drawing from a model (a cast or landscape, for example), an approach to art education he somewhat derisively termed “imitative.”

Among the media with which Hatton was proficient, she was particularly devoted to bookbinding and printmaking. During the 1935-36 academic year, she took leave of her teaching duties at KU in order to study both disciplines in London at the Royal College of Art and at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. At the Central School of Arts and Crafts, Hatton worked with direct descendents of some of the most consequential figures of the British Arts and Crafts movement, including Sydney “Sandy” Morris Cockerell (1906-1987), who taught Hatton to marble her own endpapers, gild her books, forge and cut finishing tools, and concoct recipes for binding adhesives.

Sandy Cockerell’s father, Douglas Cockerell (1870‒1945), was a leading figure of early twentieth-century British bookbinding and apprenticed for four years with Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson (1840-1922) at the Doves Bindery (1893-1921) in Hammersmith, London before starting his own bindery in 1897. When Douglas Cockerell retired in 1935, son Sandy took over the business. That same year, the younger Cockerell arranged for Hatton to acquire a set of handle letters from his father. Hatton used these tools to emboss letters on the covers and spines of her own bindings throughout her career, including the artist’s The Book of Ruth. Douglas Cockerell likely acquired the set from British engraver, photographer, and printer Emery Walker (1851-1933). The latter is best known for his work with William Morris (1834-96) in the development of Morris’s Kelmscott Press and for his partnership with Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson in the founding of the Doves Press in 1900. The Kelmscott Press and the Doves Press gave rise to the proliferation of small, artisan-driven private presses that flourished in the United Kingdom and the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Emery Walker (1851-1933), Handle letters and case, ca. 1888, wood and brass

Clara Hatton, The Book of Ruth, text scribed 1936, binding date unidentified, bound in full leather (goat)

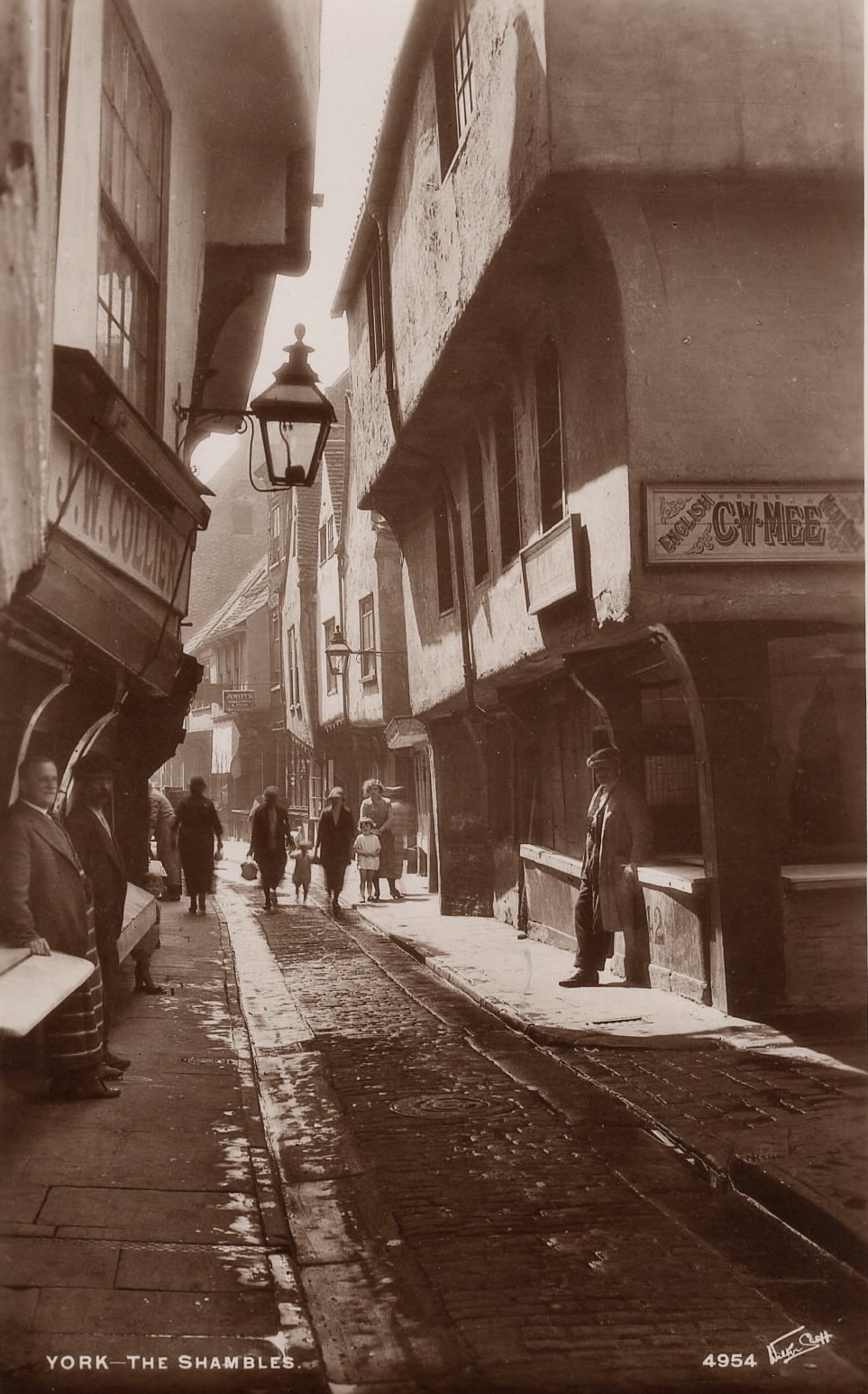

Among the graphic work Hatton produced while abroad is Shambles Restaurant (1935), a tour de force of wood engraving in which the artist renders space, light, and material with an arabesque of intricate, finely engraved white lines. In 1935 the jury of the prestigious Pennell Fund selected Hatton’s print for the permanent collection of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. The Shambles, a street in York, England, was once the location of many butcher shops. The name is thought to derive from the Anglo-Saxon Fleshammels (literally “flesh-shelves”), the term for the shelves on which butchers displayed their wares.

Clara Hatton, Shambles Restaurant, ca. 1935, wood engraving on paper

York - The Shambles (London), ca. 1935, postcard

Although Hatton received instruction in block printing as a design student at KU, her first foray into intaglio printmaking was in Rockport, Massachusetts, at the Rockport Art Association’s Summer School of Art under the instruction of American painter and printmaker Albert Thayer (1878‒1965), a Boston-area artist. Alley (1928), according to the artist, was the “very first etching I ever made. Made in Rockport.” The etching was included in the 1933 exhibition of the Society of American Etchers (formerly the Brooklyn Society of Etchers), a prestigious annual exhibition showcasing the state of American printmaking.

Clara Hatton, Alley, 1928, etching on paper

Hatton was fluent in methods from each of the three major printmaking families: relief (woodcut, wood engraving, linoleum cut); intaglio (aquatint, etching, engraving, drypoint, mezzotint); and planographic (lithography). Over the course of her career, she created and printed designs for over sixty unique images, gleaning her subjects from observations of everyday life and experiences. Views of domestic architecture, street scenes, homesteads on the Kansas prairie, industrial architecture, historic architectural monuments, and agricultural scenes provided fodder for the artist’s graphic output.

Clara Hatton, Spring Sunshine (14th Street, Lawrence, KS), 1934, linoleum cut on paper

Clara Hatton, Bowersock Mills (Lawrence, KS), 1936, drypoint on paper

In 1936 the Division of Home Economics at Colorado State College of Agriculture & Mechanic Arts (now Colorado State University) in Fort Collins hired Hatton to teach art. A gifted professor and administrator at the school for three decades, Hatton built and transformed the art offerings of the Division of Home Economics into an independent, degree-granting art department within the university’s College of Science & Arts, which is now CSU’s Department of Art and Art History. A lifelong learner, she used her 1944-45 sabbatical to earn an MFA in design and the graphic arts at the storied Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, the fountainhead of mid-century design in America. Her MFA Thesis, Design and the Graphic Arts, presents a history of printmaking and the graphic arts and features examples of Hatton’s printmaking, typography, and design. Among the images illustrating her thesis is Hatton’s graphic interpretation of Aesop’s fable, “The Leopard and the Fox,” a work that brings to bear the artist’s skills as a printmaker, typographer, and bookmaker. When Hatton was at Cranbrook, she made the acquaintance of Carl Milles (1875-1955), the Swedish sculptor and head of the school’s Department of Sculpture. In 1945 Milles commissioned her to create a booklet containing the text of his January 1945 address during the Presentation of Rings ceremony at Cranbrook’s Kingswood School for Girls, which she typeset by hand and decorated with wood engravings.

Clara Hatton, The Leopard and the Fox, 1944, engraving and letterpress on wove paper

Clara Hatton receiving MFA, Cranbrook Academy of Art, 1945

Painting and ceramics were also important components of Hatton’s artistic practice throughout her life. Seven years after she completed her BA in design at KU, Hatton earned a BFA in painting from the school. Picking Dandelions, painted in 1928, provides evidence of the artist’s increasing interest in painting and her aptitude as a painter. Hatton’s brushwork and sensuous impasto in Picking Dandelions are testament to the pure pleasure she took in the act of physically manipulating oil paint on a surface. Landscape was a frequent subject of Hatton's paintings, many painted en plein air in oil. She kept her paint box in the trunk of her car so she could stop to paint whenever she encountered a compelling scene. For example, she painted Pine and Aspens from a step of the cabin that her sister's family rented in the late 1930s in Buffalo Creek, a small community southwest of Denver.

Clara Hatton, Picking Dandelions, 1928, oil on paperboard

Clara Hatton’s paintbox

Clara Hatton, Pine and Aspens, 1930s, oil on linen over paperboard

Hatton also had an abiding interest in ceramics as a personal pursuit and curricular offering. Toward the end of World War II, she fought to develop a ceramics studio at CSU, despite pushback from her dean. She found an Army surplus kiln in Denver and hauled it back to campus, where she had converted a wing of a run-down, former dormitory into a pottery studio for students. She also built a pottery studio at her home in Fort Collins, converting a backyard chicken coop into a space for a wheel, drying shelves, and a gas-fired kiln that she drove to California to inspect before acquiring. Hatton was especially interested in the “copper red” glazes that had originated in China and that were popularized in the West by the British potter Bernard Leach (1887-1979), the leading proponent of what has come to be known as the “ethical pot.” Leach advocated for plain, utilitarian vessels with natural forms, which he believed imbued them with a moral and spiritual dimension, a sentiment very much consonant with the pre-industrial yearnings of the British Arts and Crafts movement. With its red glaze and simple form, Hatton’s Vase (1959) is an exemplar of Leach’s ideals.

Clara Hatton, Vase, 1959, glazed ceramic

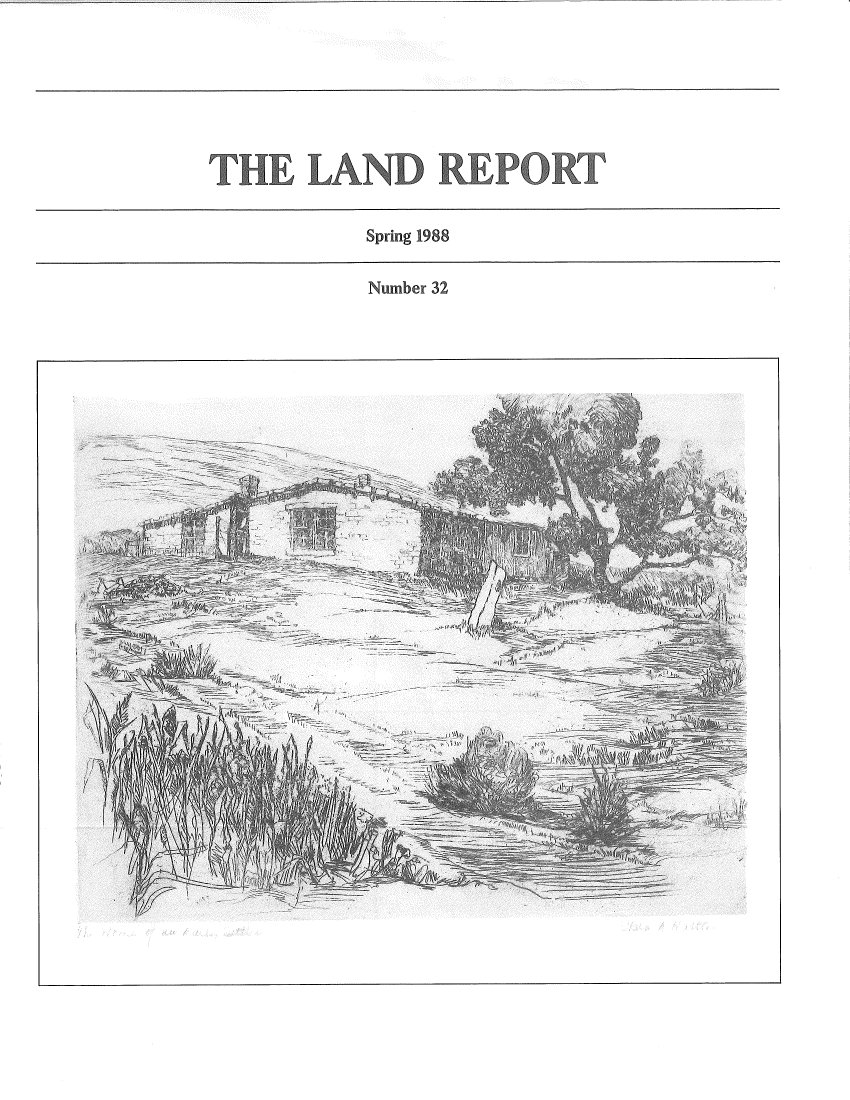

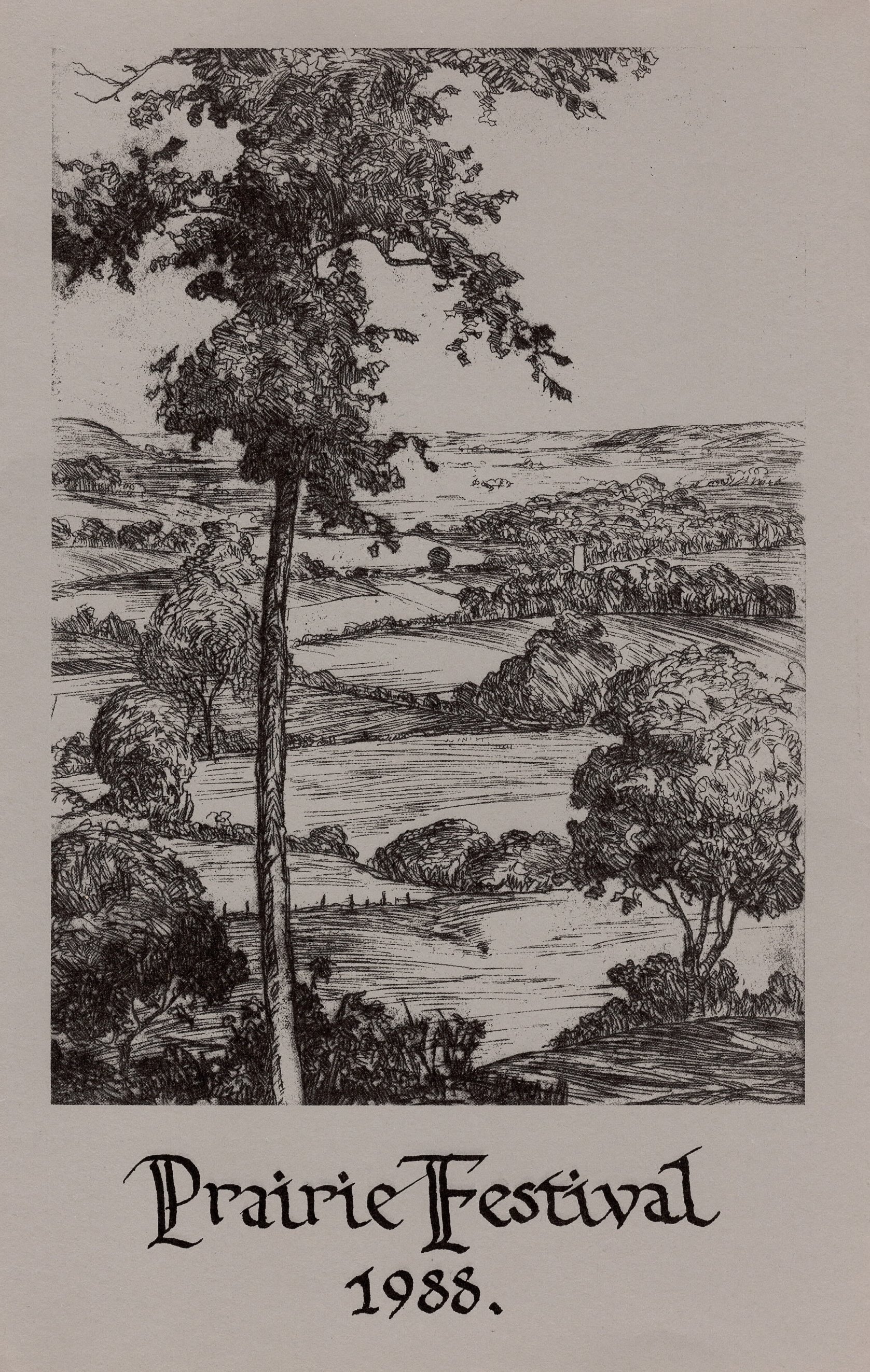

In retirement, during her final years in Salina (1970-91), Hatton continued to selflessly share her vast store of knowledge and skill, presenting lectures, workshops, and courses at numerous local art, educational, and social organizations. She also remained active as a practicing and exhibiting artist, locally and nationally. For example, Hatton’s work was featured in conjunction with The Land Institute’s 1988 Prairie Festival in Salina, an annual gathering of some of the world’s leading authors, thinkers, and artists engaged with issues related to agriculture, food, the environment, science, and social and environmental justice. In 1981 Hatton’s work was included in the seventy-fifth anniversary exhibition of the Guild of Book Workers. The organization honored Hatton posthumously with the inclusion of her The Book of Ruth in the group’s centennial exhibition in 2006. On June 27, 1991, Clara Hatton passed away after suffering a heart attack at home in Salina while tending to her garden.

The Land Report No. 32 (Spring 1988), cover; with Clara Hatton’s The Home of an early Settler, ca. 1937, etching on paper

Program cover, 1988 Prairie Festival, The Land Institute, Salina, KS; with Clara Hatton’s lettering and ‘Far above the golden valley’, ca. 1934, etching on paper (Courtesy The Land Institute)